4 Poems for Torches of Freedom reading

REFUGEES

circa 917 AD

“It will be well if we leave this country…and run away towards Ind for fear of life and religion's sake,” said the head priest. Then a ship was made ready for the sea. Instantly they hoisted sail, placed the women and children in the vessel and rowed hard. – The Qissa-i Sanjan The boat is too small for so many

and only the twin babies sleep,

drunk on milk and swaddled tight

rocking against their mother Armaiti

as the men row hard into the familiar waters

of the Gulf of Hormuz for the last time,

the starlight on the receding mountains

dimming fast until what is left

of this new moon night is the abiding

light from their holy fire, fed carefully

by their priest with sticks of sandalwood

pulled from deep in his white robes, as he looks east

into the black Arabian sea.

All the joy and blood that had come before

already turning to myth,

he counts how many generations

it takes to go from conqueror to refugee.

Gold bangles ring out as the twin babies are given

to their grandmother, then great grandmother,

and passed back to their mother, seventeen,

back erect, molten copper hair,

fawn brown eyes flecked with green,

hiding tiger, quick to anger,

as quick to forgive the every day abuses girls

seem not to know they carry.

The father Sorab, twenty-five, son of Bezon,

named after his grandfather Sorab,

the same names alternating and

reaching back into the oldest Persian towns

winding up rivers into orchards,

where they planned this winter voyage,

had four boats in sight ahead,

and six behind him,

but now they are hidden by night

as they row with speed, the wind still,

the vessels arrows through the air.

So, when tired eyes stir with the new dawn

and the babies Bezon and Avan tug with little hands to drink,

steam from their breath against her chest,

their mother lifts her head as the men cry “Hindustan!”

she does not expect rose petal beach, like silk shivering before her.

Armaiti pulls herself to her knees to look

at this land at the waters edge that shifts and stirs

as if it is made of wings disturbed by the coming of her people

only to gasp, as flocks of long limbed flamingos

rise up into the sky and scatter,

revealing a sanctuary of white beach.

SLEEP

Island of Diu, coastal India, circa 917 AD

You know that feeling, when you are caught at the edge of sleep and consciousness,

too tired to stay awake even if the world is not safe enough to rest in –

Armaiti drifts into that place –

the clouds fine lines in the evening sky;

she is falling into new earth;

Bezon and Avan are milk-white rocks at either side, smoothed into oblivion.

She reaches for the voices that talk close by

but they do not remain long enough to comprehend,

before the words flap and are out of reach.

Their priest returns and his message makes her strain to wake, but she cannot.

She keeps dropping his words like heavy stones on the floor.

She does comprehend, though, that they may stay.

WELCOME

Gujarat, circa 936 AD

A priest said: “O Raja of Rajas, give us a place in this city: we are strangers seeking protection who have arrived in thy town.” – The Qissa-i Sanjan

They are told: her people may carry the past with them, every building, every word, even God, but they may not give it away to their new country.

They can remember, but they may not feed their old stories to their new neighbors as if they are the true God’s food. They say, though there are many gods here, respect ours but do not give us yours.

They are told: keep your stories whole but separate.

They are told: keep your fire lit, cut wood for it in our forests, grow your own trees on our land, but do not take our children into your temples.

They are given jungle that stretches as far as the eye can see to a river. They plant their seeds from their old home, pomegranate, rose, sandalwood.

The local builders sit with them and plan homes. The sea is rich with rawas and mackerel. Dolphins call in the evening light. They teach the locals how to build better boats and plant orchards and flowers like their Persian gardens.

They flatter their new countrymen and add Krishna to their makeshift altars as they dig wells, and chop wood. The Portuguese arrive with Christ, they take him in. Worship the old gods, indulge the new.

Their fire burns quietly, it does not feast, it does not spread. They keep their promise.

For centuries, their numbers are small, then diminish. They have been too modest.

Is it the price of real civilization?

“Refugees” received an International Publication Award with The Atlanta Review

MOTHER’S DAY

I have traveled ten thousand miles with you,

From a small apartment at the edge of the water

in a city piled high into the sky—

Stacks of cement boxes with bathrooms and bedrooms

Furniture, people, parrots, dogs, washing machines

And the rare laburnum tree with bunches of gold flowers

That breaks the steady state of squalor that marks these

Still beautiful Bombay streets—

To rural Virginia where in the spring, lace white pear trees

Make the world seem perfect, no underlying hint of violence

Or suffering to mark what is coming for each of us.

When you think of me,

Irritable, home sick, carrying my burdens badly,

Burying my laughter deep,

Don’t forget that I see a red cardinal shooting across a brown garden,

A piece of blue sky,

An orange sunset over a wide river.

When I think of you,

Lonely, too attentive to daytime TV

That keeps you connected to the outside world,

Don’t forget that I see

The laughter of generations in your heart

In languages so old all human secrets are safe with them

Turning yellow and stale with under use.

There are many things that make a life,

One of them is love, the acceptance I have of you.

But what of laughter, mother, will it not help

When it is the end and there is nothing to mask what is coming for us?

What will abide if my children do not know Gujarati

And cannot laugh with us at our old family jokes?

But then I look around the room and see

my children laugh a lot anyway,

Like wild flowers they find a crack in the concrete

to burst out and reveal that

The time has come to forgive myself for what we have lost

And learn to live again in a new country with pear trees.

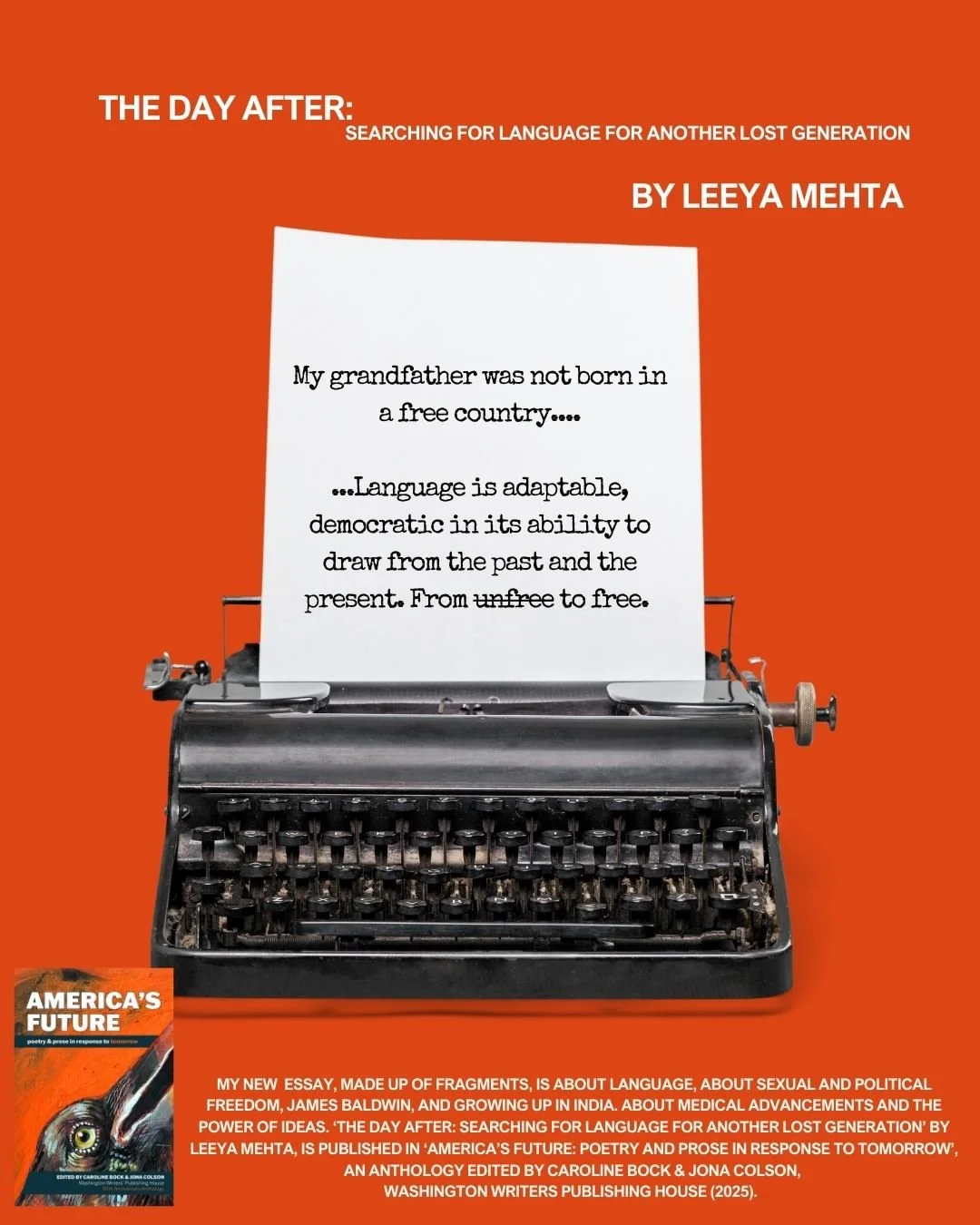

The Day After

In September 2025, the Washington Writers Publishing House published ‘The Day After’, an essay I’ve been working in their print anthology in celebration of their 50th Anniversary. I hope you enjoy it - available in print wherever you buy books.

A Trail of Breadcrumbs

Reading is like that sometimes — birds hatch and sing with familiar songs.

Close to the End

When the dog sees how happy she is he licks my legs. I do not like my legs licked so profusely but I let him do it.

The Company We Keep

When we chronicle the life of another, even with little inconsistencies, we don’t make the life of the other person whole. Instead, we seek the company of others as a way of making our own life whole, fitting missing pieces of melody into our own life’s symphony.

The Abduction: essay

An essay on The Abduction, originally published on the Beloit Poetry Journal blog.